The 239Alferov satellite, developed by Geoscan on the Geoscan 3U platform, continues its scientific mission by recording space events using a gamma-ray spectrometer. As of February 10, 2026, the instrument has detected three gamma-ray bursts, including the bright GRB 260101A. This event became the first major result of the gamma-ray spectrometer’s operation and confirmed its ability to detect gamma-ray bursts and transmit data for astrophysical research.

In this article, we’ll share details on how the gamma-ray spectrometer operates, as well as how data are transmitted and verified. We’ll also explain how Geoscan’s engineering solutions used in the satellite’s design help scientists observe cosmic events.

Studying gamma-ray sources with 239Alferov

Gamma-ray bursts are brief, powerful flashes of gamma-rays that accompany some of the most extreme energy-release events in the Universe, such as supernova explosions and neutron star mergers. They are among the brightest phenomena in the Universe, yet scientists still do not fully understand which progenitors give rise to different types of bursts or which processes generate such intense radiation.

To understand the nature of each burst, researchers need to observe its source across the widest possible range of wavelengths and involve as many space- and ground-based observatories as possible. The 239Alferov CubeSat, built by Geoscan, has joined these efforts: its data will help precisely localize burst sources and refine their parameters for follow-up observations.

An up-to-date heat map of the high-energy particle background

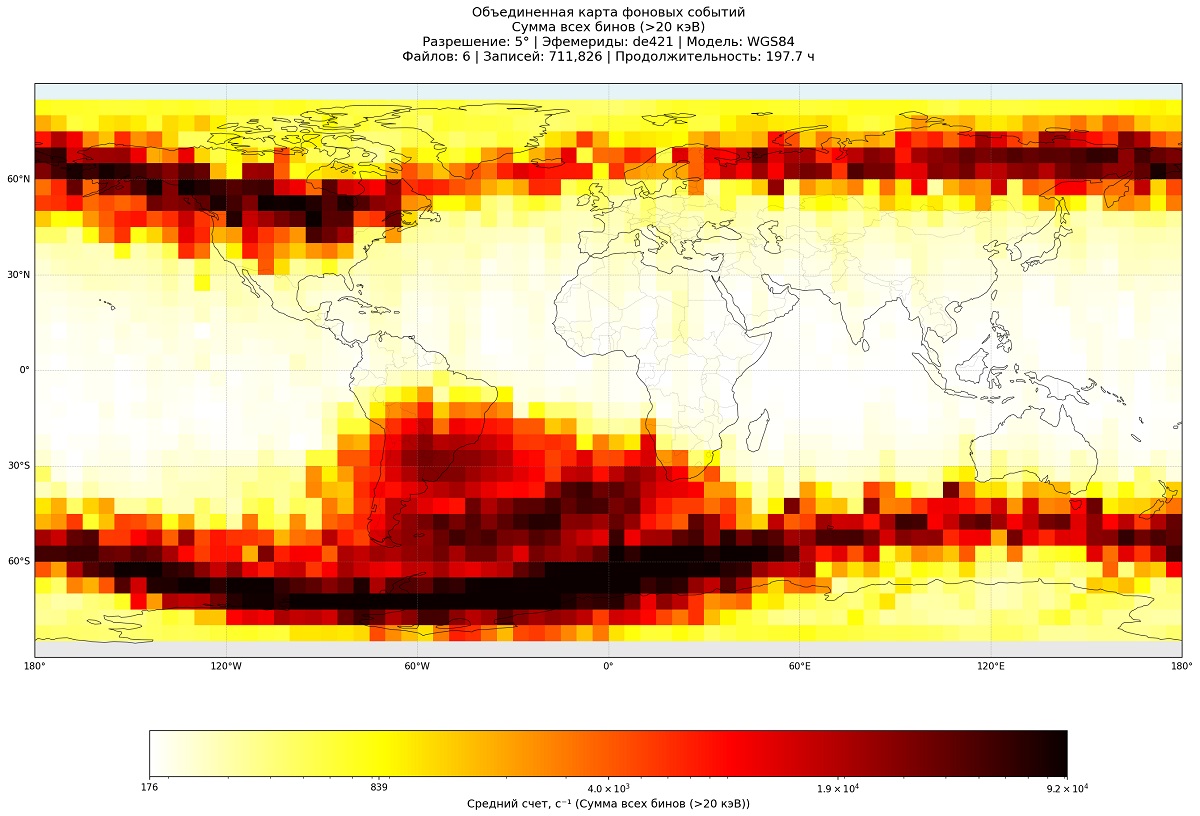

One factor that complicates the operation of a gamma-ray spectrometer in low Earth orbit is regions with increased background radiation, such as Earth’s radiation belts and the South Atlantic Anomaly. In this article, “background radiation” refers to ionizing radiation detectable by the gamma-ray spectrometer. It includes high-energy charged particles (primarily protons and electrons) and high-energy photons (gamma rays).

In regions where the background is relatively stable, the instrument can detect gamma-ray bursts by using the background level as a reference and flagging events that significantly exceed its statistical fluctuations (natural variations). However, in areas with increased background radiation, the gamma-ray spectrometer cannot reliably distinguish gamma radiation from charged particles that drive large background variability, and it cannot detect gamma-ray bursts. Data from these regions must be excluded from analysis.

To filter the data, scientists use heat maps. These maps show background intensity across different parts of the orbit, making it possible to identify areas with elevated background levels. Geoscan engineers also produced an up-to-date heat map based on data recorded by 239Alferov in October 2025. It matched publicly available models, confirming the quality of the data and the correct operation of the gamma-ray spectrometer.

The up-to-date heat map of high-energy particle background. Brightness levels reflect the background intensity in different orbit regions, including the radiation belt areas and the South Atlantic Anomaly

High-speed transmission of large data volumes

Geoscan’s main engineering task is to receive valid gamma-ray spectrometer data from the satellite and deliver it to the Ioffe Institute for analysis and interpretation.

Data is transmitted from the satellite to Geoscan’s X-band ground station on a regular basis, typically every few days. The X-band link is critical because it provides sufficient bandwidth to downlink large volumes of gamma-ray spectrometer data to Earth in a short time. This enables timely data delivery, analysis, and near-real-time response to detected events.

Detecting a proton event after a powerful solar flare

The gamma-ray spectrometer aboard 239Alferov detects not only extragalactic gamma-ray bursts, but also other gamma-band phenomena — within our galaxy, on the Sun, and in Earth’s atmosphere — and it can also be used to monitor the radiation belts.

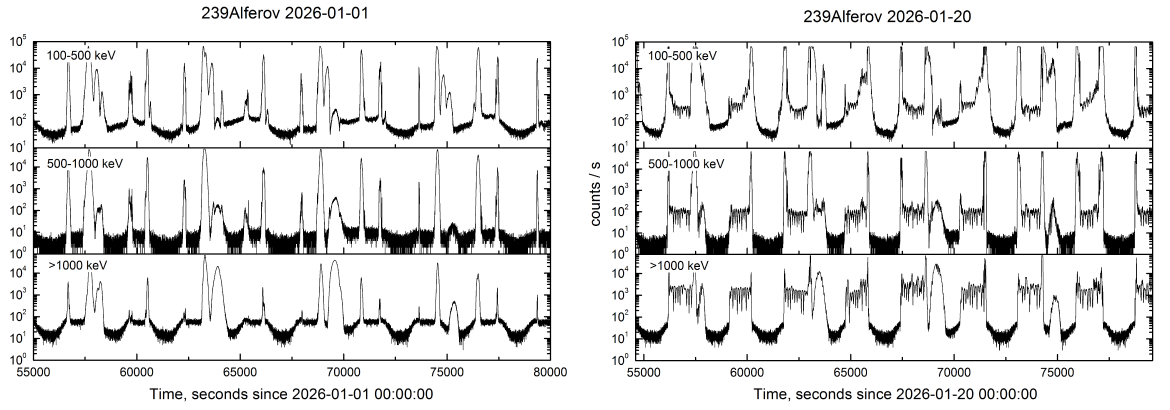

In the January 2026 239Alferov dataset, it is possible to track the impact of a proton event (a burst of accelerated particles) associated with a powerful solar flare on the radiation belts. The plots below show the detector count rates in several energy bands on January 1, when solar activity was low, and on January 20 after the flare. Sharp peaks correspond to passes through regions with elevated fluxes of charged particles.

On January 1, background levels in the polar and equatorial regions are similar. On January 20, during the proton event, the count rate at polar latitudes increase several-fold, while changes near the equator are more modest – there, the detector primarily sees cosmic gamma radiation against the usual background. This pattern is typical of solar proton events and indicates that the detector is responding correctly to changes in the orbital radiation environment.

2026. Plot 1 (left): Detector background in orbit on January 1, 2026. Stable count level in polar and equatorial regions

2027. Plot 2 (right): Change in detector background on January 20, 2026, following a solar flare. Significant count increase in polar regions

Detecting a gamma-ray burst

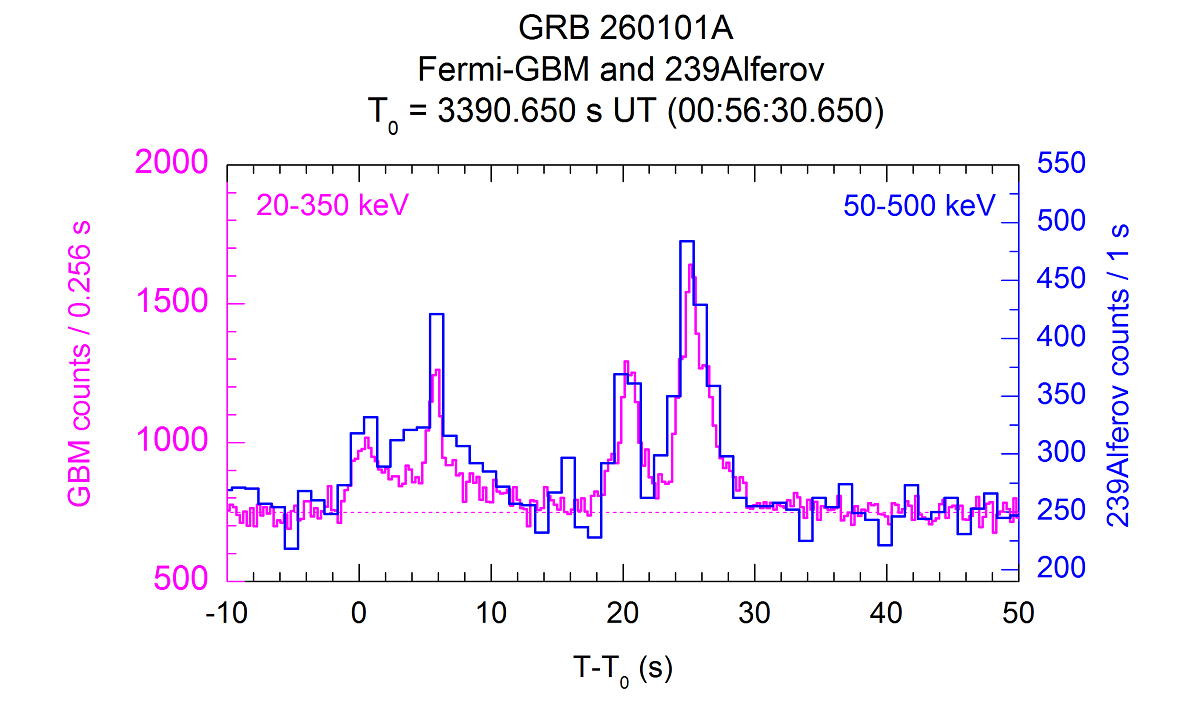

Thanks to a detailed analysis of the background environment, researchers at the Ioffe Institute also identified an extragalactic gamma-ray burst in the 239Alferov data. The record contained a short interval where the detector count rate rose well above the background level expected for that part of the orbit. The team then cross-checked the event against data from other instruments to confirm that the detected burst was real. GRB 260101A was also detected by several space observatories, including Swift, Fermi, Konus-Wind, SVOM, and GECAM-B.

Comparison of the GRB 260101A gamma-ray burst light curves from Fermi-GBM detectors and 239Alferov. The plot shows the count rate per second. The excess above the background level (shown as a dashed line) corresponds to the gamma-ray burst detected by both instruments

Based on observations of GRB 260101A, researchers at the Ioffe Institute reported the 239Alferov detection in a NASA-hosted GCN circulars. GCN circulars are a system for publishing brief reports on space events, including gamma-ray bursts. These circulars help scientists quickly share observational results and respond to important discoveries, enabling other teams to confirm the event and configure their instruments for follow-up observations.

Precise synchronization with global time

A Geoscan-developed GNSS receiver module is installed aboard the 239Alferov satellite to precisely synchronize the spacecraft clock with global time. Accurate timing is essential for detailed data analysis and for localizing a gamma-ray burst on the sky using triangulation. In particular, localization relies on multiple spacecraft recording the same burst with timestamps precisely synchronized to global time.

Precise synchronization makes it possible to determine the location and point ground and space-based telescopes to the region where the burst afterglow can be observed – the light that remains after the main gamma-ray emission. This glow provides additional insight into the physical processes at the time of the event and helps refine the source localization.

Further tuning of observation and data downlink modes

At present, 239Alferov records data continuously, with downlinks occurring every few days. In the future, the onboard software will be updated to allow the gamma-ray spectrometer to be switched off in high-background regions identified on the heat map. This will extend the satellite’s operational time and reduce the number of false triggers from the gamma-ray spectrometer.

“Geoscan is currently one of the leaders in developing CubeSats and onboard systems for them. The company’s team has experience building applied instrumentation based on a range of physical principles. Developing the gamma-ray spectrometer and the spacecraft at Geoscan provided greater flexibility in selecting observation and data downlink modes, which should deliver meaningful scientific results and provide the experience needed to develop follow-on experiments for observing gamma-ray bursts,” commented Dmitry Svinkin, Senior Researcher at the Laboratory of Experimental Astrophysics, Ioffe Institute.

In July 2025, Geoscan-6 – also equipped with a gamma-ray spectrometer – was placed into orbit. The satellite is currently in its commissioning and testing phase, which includes calibration, attitude control system tuning, and verification of all onboard systems. Once commissioning is complete, Geoscan-6 will be ready for targeted scientific work, including observations of gamma-ray bursts and other astrophysical phenomena.

The 239Alferov is a nanosatellite built on Geoscan’s 3U platform. It was developed for the Space-π program under the Innovation Promotion Foundation, commissioned by Presidential Physics and Mathematics Lyceum No. 239 and the Zhores Alferov Physics and Technology School. The small spacecraft’s payload includes a gamma-ray detector and the VERA ablative pulsed plasma thruster. The satellite’s transmission frequencies have been coordinated with the International Amateur Radio Union (IARU).

239Alferov became the first spacecraft in the Space-π “Supernova Hunters” specialized constellation of the Innovation Promotion Fund to detect a gamma-ray burst. Additional small astrophysical satellites are scheduled for launch in 2027. Three of them will be developed by Geoscan in cooperation with the Laboratory of Experimental Astrophysics of the Ioffe Institute. The first satellite in the series will also involve participation from the Autonomous Nonprofit Organization “Development of Space Education.”

You can find more information about gamma-ray bursts detected by Geoscan-developed astrophysics satellites on our portal.